A few weeks ago, I wrote about small numbers of patients consuming large and disproportionate shares of health care goods. The thinking being, if we focus efforts on outliers, hospitals will save money and FTEs by economizing in the right places. Why waste resources on interventions applied to fifty percent of the hospital population when only ten or twenty will do.

While dogma still holds, i.e., a few folks will always consume the greatest slice of the health care pie, we tend to view the statistic at a population-based and not individual level.

A recent release from Health Affairs should force us to reconsider our assumptions: For Many Patients Who Use Large Amounts Of Health Care Services, The Need Is Intense Yet Temporary The study investigators probed to determine whether a cohort of high-needs people who received the label “outlier” remained static over time. A first of its kind study.

If this is so, identifying them would be advantageous, as structural changes in their care delivery would alter their trajectory in the health system in a salutary manner. Obvious. Essentially, once an outlier, always an outlier and the health state a high utilizer possesses will continue with them throughout their lives. We do well by identifying them early.

What they found surprised me. The study took place at Denver Health, a large urban safety-net integrated delivery system, between May 1, 2011–April 30, 2013. The investigators conducted a cross-sectional and longitudinal analyzes of 4,774 publicly insured or uninsured super-utilizers (of n=214,000 or 2% of the population). They defined super-utilizers as having three or more hospitalizations in a rolling twelve-month look-back period or both a serious mental health diagnosis and two or more hospitalizations in the same look-back period.

What did they find?

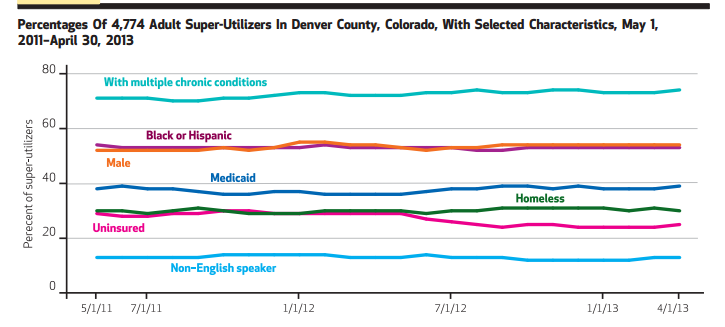

First, the graph below confirms the fixed nature of the cohort. Over time, characteristics did not vary (uninsured dropped in 2012 post-ACA):

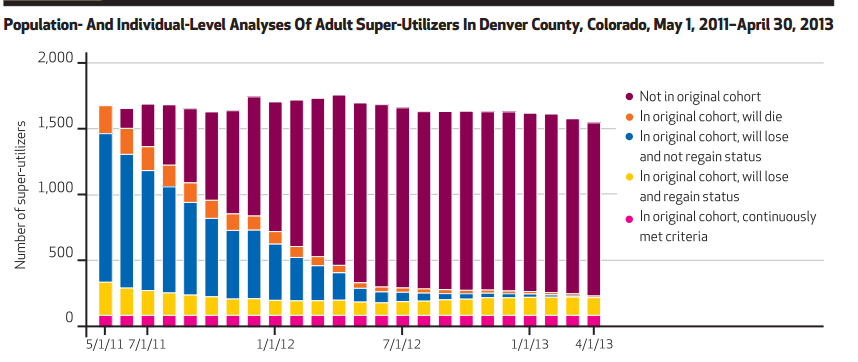

However, the decay in who started and then exited the group was rapid and profound:

At the end of two years, only fourteen percent of patients endured in the original set. Subgroups who you might expect to remain, as those with mental health diagnoses and multiple chronic diseases, were not durable in their presence. They came and went. Only patients receiving inpatient hemodialysis remained constant (a minority within the population–see exhibit four in the paper [gated]). Recognizing the heterogeneity of these super-utilizers makes the well-established identification tools we have come to rely upon less potent for sure.

The author’s state:

More research is needed to answer important questions related to super-utilizer identification, program design, and program effectiveness. Improved predictive modeling should aim not only to identify individuals who are likely to experience sustained levels of avoidable utilization, but also to better classify subgroups of patients for whom aligned interventions are needed.

We spend gobs of time speculating and studying variables that may allow better identification of high-risk individuals. Denver Health probably has applied interventions to address many of them, e.g., complex care committees and integrated rounds. Yet, if they had a dominant effect, as patients presented for hospital admit one, recidivism rates and costs would diminish, and the endless enter and exit cycle would moderate. They would apply what works, and the horizontal bars above would decrease in height over time with the concurrent drop in super-utilizer numbers.

That’s not to say Denver staff did not make a dent–they probably did. However, it is hard to tease out hospital effects versus those of mother nature or the external community, i.e., patients getting from point A to B with or without institutional help.

Nature abhors a vacuum, and when one group of patient loses their Medicaid eligibility, another gains it; when the local Walmart begins to hire, K-Mart cuts their staff; and when one group of folks finds the patience to wait and receive their mental health services or shelter, the other walks away in frustration. We have limits in what we can predict and identify.

As such, how tools like the LACE score can inform us remain specious at best (I’m not a fan), as this study indirectly shows. Gestalt will trump Dr. Watson for the near future because what occasionally seems like a no-brainer evolves into something more complex. People’s lives have too much nuance and hinge on intangibles we don’t capture in administrative data or routine questioning. White matter CPUs still trumps silicon stock.

The near term, abacus over calculator, sensitivity over specificity prescription may be: a) the floor staff team identifying who is at risk using best judgment (~30-40% of beds), and b) applying the four or five things at discharge we know produce. With some exceptions, trying to game out the second figure above with our current prognostic tools will lead to little juice and many inefficient and wasteful squeezes.

Leave A Comment