Given the signs Paul Ryan, Speaker of the House, has flashed during his tenure, expect phase one of the health care financing overhaul to be heavily focused on Medicaid. The incoming administration aligns with this change (#6), as does the president-elect’s choice of Tom Price for HHS Secretary. This turn will have an impact on hospitals and something you should pay attention to. You will see lots of press over the coming months, and you will hear the term Medicaid block grants. You should have an opinion, especially if you work in a rural, safety net, urban, or academic medical center. I would imagine that holds true for many of you.

Medicaid began in the 1960s, and unlike Medicare which is s a federal program–identical throughout the country–Medicaid is a means-tested program shared by the feds and the states. Why? Mostly because of views on poverty, federalism, and race when Congress passed the bill. In a nutshell, blocks of states in the south desired control of how they assigned care and spent their money.

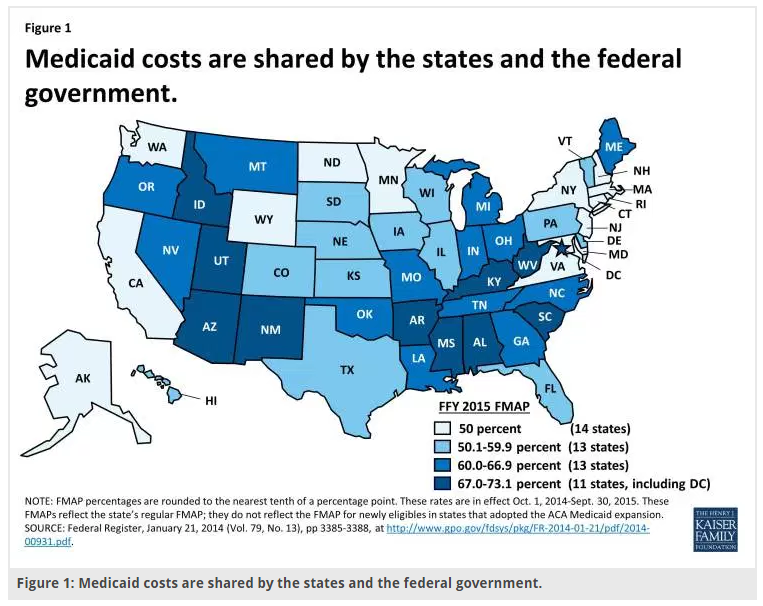

Thus, legislators instated a system of shared financing and that arrangement still exists today. You may have heard of the FMAP (Federal Medical Assistance Percentage), and it’s the split the feds have with states each time they dispense a dollar. In NY for example, for each fifty cents the state puts out, the feds kick in fifty. Here is how they receive their allocations (note the individual state differences):

At present, Medicaid covers seventy million people and expends a large part of both state and federal budgets. With an open-ended construction, states can potentially spend without limit—which can lead to gaming and waste as they procure more support and consume (we would like to presume all fifty put it to 100% beneficial use, but life being what it is, etc.).

Each state is also unique in the way they administer their program, and benefits, payment rates, and eligibility differ (just have a look at doc reimbursement from state to state). Regardless, the growth of Medicaid over time has been significant, especially post-ACA. Most of it stems from more patients, sheer numbers, and not by way of intensity of individual spending.

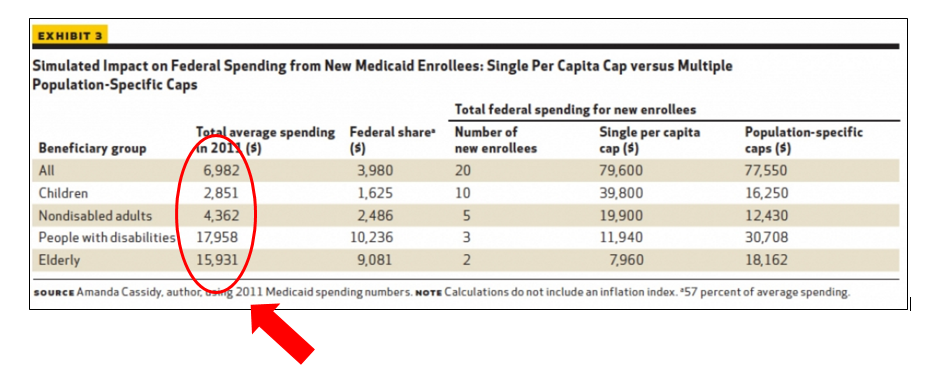

However, because the program has such a diverse charge, the types of folks participating contrast: children, disabled adults (cognitive and physical), elderly poor on Medicare, otherwise known as dual eligibles (including those within nursing homes), and able-bodied adults. Medicaid has become that prototypical hospital building we all know that keeps getting repurposed with odd connecting bridges, hallways with false walls, and strange corridors with unused computer equipment piled high. All manner of vested parties tack on new folks, and each new group incurs costs at varying levels. Have a look:

Now getting to block granting Medicaid, it would entail providing states a lump sum for maintaining pre-ACA eligible participants in the program. Think of it as a global payment with the effect of freeing the federal government of their unlimited financial obligation—a surefire way to curtail growth.

Defenders of that approach like the idea of turning control of the dollars to the states. Each would have a looser hand in designing their program: states with greater urban populations may want to spend more on care delivery in clinics, and rural states may wish to focus on telehealth and mobile providers. The catch, however, is designing a block grant at time zero that inflates with unexpected costs of care.

For example, providing expensive new treatments and adjusting the reimbursement formulas if the economy undergoes stress and unemployment rises and folks lose coverage from other sources. Right now, that is the intangible, and we do not know what the incoming leadership has in mind.

Alternatively, a modified approach to a straight block grant, states can receive allocations based on categories of patients like those listed in the table above. The federal government can assess demographic and administrative data to determine how many kids and disabled adults need coverage and decompose the total into appropriate fractions. A state might receive three thousand dollars for each child, twenty thousand for each disabled adult, etc. But again, establishing a growth rate year to year would require forecasting and speculation—not exactly settled science.

Additionally, spending under per capita cap proposals would undoubtedly vacillate based on changes in the balance of the patient classes, i.e., twenty percent of a population might have disabilities in one year and twenty-two in the next. However, to reiterate, those corrections would not account for changes in the costs per enrollee beyond the predetermined growth limit set at the outset. If a pharma company discovers a cure for sickle cell disease and the treatment cost $125K per year, current methods to remunerate states would not cover the overruns. It would be like me paying you a cost of living increase of three percent per year only to have your gas, housing, and food costs go up five percent several years after we ink our agreement.

In either scenario, if the apportionments are inadequate and the states cannot smooth out inefficiencies faster than declines in support, states will have three options: reduce benefits, reduce eligibility (waiting lists, capping enrollment or altering requirements), or cut provider reimbursement. And keep in mind, states cannot cap the disabled, pregnant women and low-income children out of the program by law. Instead, the target would be many of the folks we currently care for, like adults and less well-off seniors. Also of note, the types of Medicaid reductions Congress has suggested entail big numbers, on the order of one-third over ten years. With machete like precision block grants do the job. States get a lump sum, the carrot, but it may not be enough.

How then might this affect hospitals?

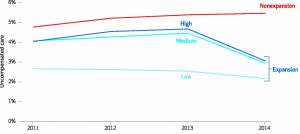

Below, you can see in states that expanded Medicaid post-ACA the drop in hospital uncompensated care rates. A few percentage points make a difference as hospital margins are slim, so these reductions have significance. The high, medium, and low categories denote the burden of uncovered persons’ expansion states had before the ACA.

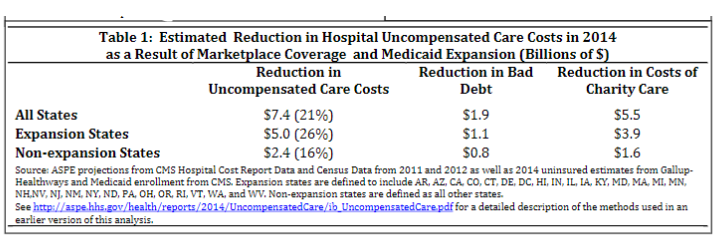

And in another view, you can see the reductions broken out by bad debt and charity care in absolute terms:

The crux of all this, though, is the hospital industry “agreed” to ACA directed reimbursement cuts, with the concurrent expectation from Congress they would step up their productivity (see here). In turn, facilities counted upon more insured lives entering their doors. Hospitals got them.

However, with a Medicaid recalibration in 2017 or 2018, some patients will lose or see their current coverage decline; and with block grants, fewer dollars will trickle down to providers. If states can deliver the same services more efficiently within a few years of the conversion, no harm done. I do not anticipate that happening, though, so here is what we might encounter:

- More managed Medicaid and restricted networks–Most states now have commercial insurers overseeing their programs. States pay the companies, and in turn, insurers administer the programs. With an emphasis on cost, MCOs will pick and choose hospitals based on multiple grounds, presumably on value—but seeing we cannot measure it well, expect randomness.

- Provider Cuts–If states or plans wish to avoid trimming patient rolls or cutting benefits, reimbursement will decrease. You can do the math. Medicaid costs per enrollee are already low and thus, the delivery side would take it on the chin (think Medi-Cal).

- Exchange Options–States may opt to use their grant money to fund exchanges and offer patients non-Medicaid commercial plans. See #1, but only now the restrictions will go through private channels.

- More denials of care–Needs no explanation. It happens now and will occur in the future—but up the stakes.

- Cost shifting— As Medicaid reimbursements drop below sustainable levels for providers, demands will ratchet to non-Medicaid commercial plans and Medicare. Hospitals often invoked cost shifting as fact in years past, a phenomenon most health economists disavowed. However, now we may get the real deal.

- No givebacks–The federal government will not open the purse to make hospitals entirely whole if the newly Medicaid-insured disappear. The pre-ACA baseline of generous support will not revert—as stated above. Peter got robbed, and Paul will not get the proceeds back. (If you want to read more on DSH payments—a “typical” at risk government support, see here.)

- Discharge planning headaches–Anticipate an inability to find post-release follow-up services for patients. With rate cuts, you can expect fewer specialty services in the community. Ditto for social supports.

- GME dollars–With less Medicaid reimbursement, GME dollars, themselves in the crosshairs, will suffer further dilution.

- Blue and red state divide–Blue states historically spent more of their dollars on Medicaid. Expect the trend to continue, and the fifty-state laboratory of experimentation will go on—but not with the best of vibes.

- Tension between the federal government and states–Governors, even GOP, will push back as Medicaid block grants may not meet the needs of their constituents.

- Nursing homes and LTC–Medicaid supports these services. A lot. As they are under stress already, more problems could be in the wings.

Each of the above will have direct or knock on effects to hospitals. Medicaid reform may yield a positive result for some system players, but at least for acute and sub-acute facilities, I envision cuts and less revenue. A few hospitals need the consolidation push, but much of the adjustment, especially at the outset, will lack direction and inpatient providers will implement in a misdirected or ramshackle manner—and it will not be of their making. Even if Medicaid comprises a small part of a facility’s income stream, with already modest and shrinking margins, institutions will feel it.

From a somewhat prejudiced point of view, Medicaid block grants make me uneasy and from the perspective of the hospital—our employers and workplaces, this transition will be formidable and potentially crippling for a select minority. Lobbyists will not go hungry.

Incidentally, The American Hospital Association, America’s Essential Hospitals, and America’s Health Insurance Plans show their cards here as it pertains to what might be in store the next few years.

“We respectfully urge you to also include in such legislation the prospective repeal of funding reductions for Medicare and Medicaid hospital services for patient care that were included in the ACA for purposes of helping fund coverage for the insured,” Richard Pollack, president and chief executive of the AHA, and Charles Kahn, the president and CEO of the FAH, wrote in a letter to President-elect Donald Trump and Vice President-elect Mike Pence.

The groups hope the incoming administration will approve the restoration of Medicare’s hospital inflation update and Medicare and Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital payments, which help facilities that care for high levels of uninsured, poor and disabled patients.

Leave A Comment