What does it mean to decrease the length of stay? Perhaps you see it as your raison d’etre or a maybe checkbox on the To Do list. To your hospital, it implies efficiency, so they save money and get more with less. Period.

However, even if you achieve a level of increasing efficiency year after year, the hospital you work in, regrettably, will still have a margin (profit) problem. I will tell you why.

My concern stems from something I read published by the CBO. Hospital-based providers will find it compelling.

First, if you do not know what the CBO is or what they do, it is hard to grasp why what they say carries so much weight. Once you are aware of the acronym, you will be amazed how frequent their name pops up in the news.

Whenever your legislator introduces a bill to do something in Washington, say, a measure overhauling how we deliver a medical service or proposing a new way to address an area of need in public health, there will likely be upfront costs. However, every bill sponsor will claim significant savings and tout the upside impact. Analogously in your hospital, every proposal the cardiologists, orthopedic surgeons, pharmacists, and hospitalists bring to the CFO all trim coin and rain puppy dogs and rainbows. You need a referee.

So multiple legislators dump a whole slew of paper down wanting to get the spotlight, help their constituents back home, make the country better plus win favors with whoever the bill might benefit.

But not every bill has a positive return on investment or the gains might not be apparent. Who does the math and steps in as the arbiter?

That is where the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) enters. Again, they play it straight and are known as numbers people, not ideologues. Their job is to inform Congress what a piece of legislation will do to the federal budget. If your bill gets a good tally, you shower love. If your bill gets a bad one, the CBO become partisan hacks and the author of the bill a hater. Keep in mind, this is hard stuff, and there is a significant margin of error in what they execute–but it is the best we have.

The pols with lobbyists in tow then make hay of the findings—good or bad—and the legislative process goes from there. Simple. But keep in mind, if your score stinks, good luck moving your bill through the chambers and landing it on the president’s desk.

The CBO also does periodic economic assessments on specific topics. Conveniently enough, one I wish to highlight today concerns hospitals.

As a reference, around 75% of hospitals have positive margins–meaning revenues exceeded costs. As the economy recovered post-recession and with the advent of the ACA and the availability of newly insured patients, they achieved gains and facilities strengthened their balance sheets. Good for big buildings with bedpans and candy stripers. The other 25%, rural and safety net hospitals, lost ground and went negative. Not so good for everybody.

However, part of the blueprint over the next decade—cooked into law–entails reimbursement cutbacks. The feds have expectations we, and I will include any hospital-based provider here as we serve as the catalysts to make our facilities run, will become more productive and do more with less. So if CMS will pay Hospital A $100 in 2016, the same hospital will get $98 in 2017. Why? Because we will become better at what we do and squeeze out waste—or so they think. This would be an example.

You can project a lot of savings if you make assumptions like that. But whether we will see those estimates come to fruition remains to be seen. Unfortunately for us, though, unless we attain those efficiency goals, many hospitals with positive margins will take a hit. A lot of them.

So what does the CBO foresee?

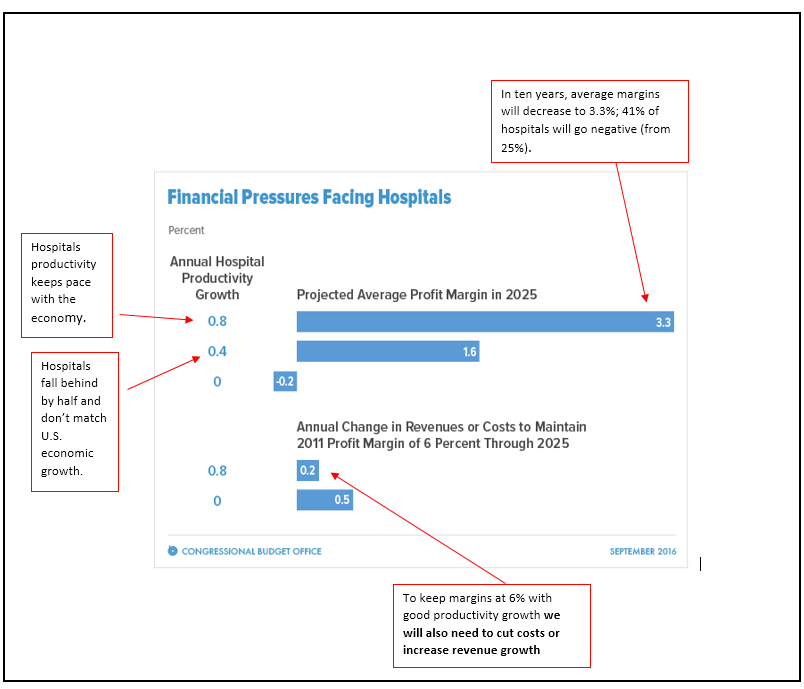

Have a look at the figure below—and keep in mind the CBO estimates the productivity growth of the general economy will be 0.8% per year. In other words, the U.S. through adopting technology or outsourcing will make slightly more widgets, about one percent, year over year using the same volume of inputs.

Again, we don’t know whether the hospital sector can do the same (we do not make widgets after all). If we assume a healthy margin in 2015 of 6%, in ten years IF WE KEEP PACE—and most hospitals have not experienced productivity growth in the past– margins will drop to 3%. How can that be?

Because there will be concurrent cuts from other revenue flows–it’s a complicated system with many moving parts–and any efficiency gains we accrue will still feel like we are paddling upstream. If we can achieve 0.8% productivity, and if we desire the same 6% margin, we will also have to increase revenues or drop our costs. That suggests we must find more patients and continue to trim–and get better at what we do concurrently.

Again, see the figure with my annotations and looming vicissitudes:

So what is a perfectly good, God fearing hospital to do? Based on current statutes and past trends, not much.

This is a fact: if things stand as they are, hospitals will lose money.

If you posit the country has too many hospital beds or they are awash in surplus cash. Or they run too inefficiently and you know they can pump out more widgets with their present resources, then you are in luck. It looks like CMS has the right prescription. However, if you feel mistaken assumptions might lead to too rapid a retrench with untoward outcomes—and that’s not to say hospital spending is correct where it is—something has to give.

The general theory is, “well, they will fix it, they always do.” They being Congress with the supposition past is prologue and repairing the oversight will just require a swipe on Uncle Sam’s AMEX card. Maybe yes, maybe no.

If you have not noticed, hospital systems have been shifting care to the community. There are richer fortunes to be mined in those parts of town. We could get some relief, but acute deficit spending for hospitals and wealthy professionals makes bad headlines, and this might be the smoothest way for Congress to deliver care where patients live rather than where they convalesce. We might get a quarter or half a loaf–all baby step like, but the watchwords for the future will be evolve or perish—and a few will. Negotiating whether your opening position begins at draconian does not bode for a celebratory end.

Here is some pudding to conclude:

The report, published this week by the Chicago-based credit-rating agency, found the average operating margin across not-for-profit hospitals improved from 3% in fiscal 2014 to 3.5% in 2015. At the same time, the average operating margin before interest and taxes also improved from 9.7% in 2014 to 10.3% in 2015.

The analysts said the rise in margins was because of “improved cost efficiencies, higher number of patients with insurance coverage and greater focus on revenue-cycle improvement and fee collections.” Hospital managers have also gotten better at managing more patients, they added.

Despite the improvements last year, Fitch analysts said they expect operating performance will be “more volatile” in 2016 and beyond as the CMS further implements value-based reimbursement models and reimbursement rates decrease overall.

The analysts predict pressures from the Affordable Care Act will fully emerge in 2016 with more labor and wage pressures for clinical staff and an increased need to address population health.

Someone is reading the CBO.

BONUS: Want to see if your hospital may be a more profitable one? Here is a good study that goes deeper. Hint. Nonprofit hospitals are for-profit hospitals in disguise.

Leave A Comment