We sat in the living room at a colleague’s home, drinking beer, wine or sparkling water, eating desserts, and talking. Talk started with residents comparing notes about clinical sites or rotations, worries about being prepared for boards, congratulations on fellowship matches, and discussions about trying to decide what to do post-residency.

“How are you doing?” my colleague and assistant residency program director asked the group. Silence followed. One person spoke up. “I’m worried about what will happen with my fellowship. I’m still talking with my lawyer.” This was not a question of where he would match, how his clinical skills would be stretched, or adapting to a new location. This was about his immigration status.

We met two weeks after the president’s executive order on immigration, and he was worried if he would be able to continue to work under his current visa, being from one of the seven countries called out by the order. More silence followed. “My mom has told me I should come home,” said another resident – this one not from one of the seven countries. There was a nervous laugh around the room.

I recall having many of my own stresses and worries during residency: Am I smart enough to be here? How do I battle exhaustion and care for patients? Will my wife and my kids still recognize me? What do I want to be when I grow up?

But concern about my immigration status? Worry that despite having a residency spot or a fellowship offer I might not be able to go or keep it? Those NEVER crossed my mind. And the idea of having to talk with “my lawyer?” Wow. Nope – never a consideration. I do not even have someone who I would consider “my lawyer.” Despite having many friends who are lawyers, I still feel a bit like talking with the lawyers is like having to go the principal’s office.

At the University of Minnesota, we have a great internal medicine residency program. We have a high match rate in competitive fellowships, and our residents deliver excellent care. Like most internal medicine residencies in the U.S., we also have international medical graduates (IMGs). The IMGs in our program receive no preferential consideration – in fact, quite the opposite. According to ERAS public information, there are 6,560 applicants for internal medicine who trained in the U.S., compared to 13,215 IMG’s. According to the NRMP, my home state of Minnesota has 113 medicine residency slots total, across all programs. Of these only thirteen went to IMGs in last year’s Match. Nationally, forty-five percent of internal medicine program interns were IMGs. The IMGs who match in our program are truly the cream of the crop. They routinely have sky-high board scores, excellent letters of recommendation, and at least several publications to their name. Many have incredible stories of how or why they became physicians, why they came to the U.S., and what they have gone through or accomplished since prior to applying to our residency. As a side note, many have already been fully trained as a physician in their home countries and often choose to come to the U.S. to do another residency

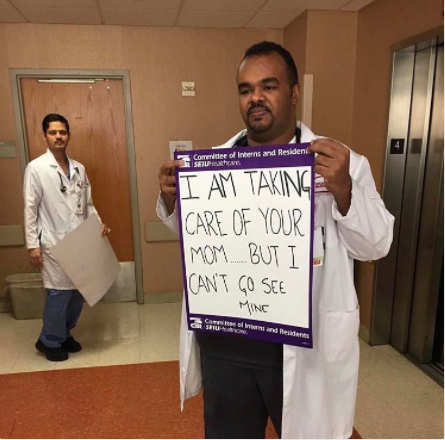

IMGs fill out the ranks of our residency programs, and many go on to disproportionately care for patients in our rural or urban underserved areas, or Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. A recent publication in BMJ has suggested that the care they deliver is equal to or possibly even superior to the care delivered by U.S. medical graduates.

In short – we want IMGs here. We actually NEED IMGs here, and our system depends on them. Our hospitals, clinics, universities, patients, and communities are enriched by their perspective and the care they deliver. The U.S. has been a choice location for immigration of IMGs because of excellent training and opportunities. This has even led to a “brain drain” as physicians leave the countries where they were trained to come to the U.S. But our choice status is in peril.

Recent lawsuits and action around the country have called the initial travel ban into question, but no matter what ultimately happens in the courts, I am troubled by the logistical and legal implications of the president’s executive order. It is the wrong approach to the laudable goal of making our country safer. But more than that, I am saddened and worried about the tone and the message it sends to immigrants and refugees in our country. I have had physician colleagues whose families have urged them to leave. One colleague’s in-laws have already left the country. It is yet-to-be-determined how this year’s match will be affected. Programs may fear that IMGs who have matched may not be able to obtain a visa, rendering them unable to come to the U.S., leaving a program unfilled. Fear over immigration may lead fewer of the best and brightest IMGs to apply. Our residents, our programs, and ultimately our patients will suffer from this.

The gathering I mentioned earlier included many of our residents who are IMGs. It included a new hospital medicine faculty, two chief residents, and several other talented residents with excellent bedside manner and patient care skills. They have completed important QI projects and taught our medical students, and some began research and publications or presentations in their intern year. They hailed from Nepal, Thailand, Nigeria, Egypt, and Syria, to name a few.

Regardless of their country of origin, they all expressed concern about the president’s order. Behind the chuckle about the worried mother, there was real worry. Many of them felt betrayed by a country they had all worked so hard to get to for residency, and many felt unwelcome. If we lose these colleagues because they do not feel welcome, we will all suffer.

I know that the Society of Hospital Medicine strives to be a big tent for hospitalists of all kinds, and I know that many of us have differing political views. But I hope that we can agree that IMG’s provide a major benefit to residency programs, hospitals, and patients. I have been impressed by the AAP and AAMC standing up for inclusiveness and expressing concern about the president’s executive order. If I had my way, all specialty societies (including SHM) would take firm stands affirming the benefits that our immigrant or refugee colleagues bring. We owe it to our friends, colleagues, trainees, and patients, and we should also go out of our way to them know they are welcome.

Leave A Comment