If you have given any thought to corporatized medicine and its impact on medical practice, I advise you to read this extended New York Times piece:

The story concerns the contentious relationship between a hospitalist group and their employer, PeaceHealth Sacred Heart Medical Center in Springfield, Oregon. The group alleges the hospital made advances to replace them on account of their suboptimal performance–both financial and professional. Sacred Heart put out bids to national companies to outsource their inpatient line of business. However, their plan did not move forward due to significant physician backlash. Feeling vulnerable, the docs chose to join a union and hitched with the American Federation of Teachers, which already represented nurses at Sacred Heart.

Negotiations continue, and the article concludes with an ambiguous tone: pay, hours, and performance swirl together in a he said, she said lingering dispute.

Given the climate we work in today, you should not put the piece aside without considering where you stand on the group’s choices. Threats of corporate takeover, greater regulatory oversight, hospital downsizing, and subsidized salaries make hospital employment a vulnerable target for disruption. No one feels secure. While we are all sympathetic to the little guy, and that includes me (I am one), the healthcare realm has many points of view. Depending on geography, culture, and market performance, those points of view will vary.

A few comments on the article.

For one, the writer has sympathy for the hospitalists and the piece skews heavily in their favor. He renders the conflict more David versus Goliath rather than two “equal” parties seeking to adjudicate differences. We do not get much in the way of metrics and what the hospital expects, nor what the physicians deliver. To pass judgment, I would have liked more data. Further, we only meet a handful of the principals and more individual accounts of what transpired would lend additional substance to the story (I’m sure space restrictions limited comments).

It’s hard not to side with the hospitalists–especially being one, but I wanted to approach the disagreement with a more objective lens. It just was not there. The hospital was also non-revealing, and they did not disclose details on what they foresaw the inpatient overhaul accomplishing beyond usual platitudes.

In evaluating the many remarks left by readers, however, most parallel the one below–and likely reveal the collective sentiment of the public:

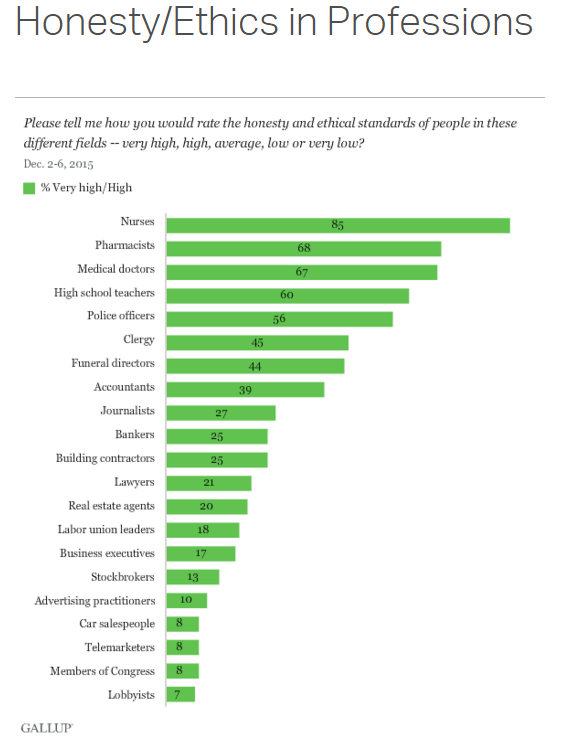

Offer up physicians and big bad acute facilities, and you can bet who will prevail. While most folks value their local hospital–and indeed they sit way atop MCOs, pharma, and DME manufacturers on the lovability scale, they still value their caregivers more. Take your case to the people and present an unsympathetic corporate parent and odds are, you can predict the victor and the vanquished. Need proof? Here’s the 2015 Gallop Poll on the most trusted professions in America:

Within the public consciousness, health personnel, despite their wrinkles, are still held in the highest esteem. The tone of the article and response of readers, again, do not surprise me and are consistent with long-held views.

The article also does not explore the nuances of forming a doctor’s union and the difficulties it might solve (or create). I am no expert, but:

- Doctors do not strike. They cannot and never will (not so in other countries). What hardline options does that leave?

- Can union officials actually provide a doctor secure employment? They may assist in removing barriers to unreasonable restrictive covenants or more favorable benefits (not trivial), but if a hospital or group wants to nudge you out, they can make your life uncomfortable and unwelcome enough to show you the door.

- Does collective bargaining work for the learned professions like it does with the trades?

- Can a union lobby or litigate more efficiently for a few members rather than a professional society speaking for thousands (who may face the same issue)? Can opposing sides also belong to the same society and expect equal advocacy?

- Despite being admired by the public, their admiration for professionals only goes so far. Sympathy for overworked and underpaid family practitioners holds some weight. Not so much for interventional cardiologists with fast red cars. Crappy economies also have a funny way of changing perspectives: the same public can fall out of love quick and our job security can sink with theirs.

- Does a teachers’ or any non-medical “surrogate” union understand the balance between physician efficiency, safety and quality of life (or healthcare for that matter) in a complex field–especially given the paucity of data on the subject?

- If consolidation continues and a majority of physicians work for organizations, will anti-trust laws change and formal alliances develop with or without the consent of organized medicine?

- Is the corporatization of healthcare inevitable? Will unions be the only effective counterweight, and if not, what else?

The list could lengthen, and the issue of whether doctors should unionize requires more expertise than I possess. It’s a black box to me, and I have more questions than answers. But the piece offers a starting point and gets us to imagine a future none of us now envision.

Ask yourself, what would you say if a colleague asked you to join a union? That’s as a good a step one as I could imagine.

The conversation turned, inevitably, to the dreaded “skin in the game.” I wanted to know what, exactly, they considered so offensive about having a financial stake in the hospital’s performance.

Dr. Schwartz responded by recounting the first time he had heard the expression, at a meeting with the hospital’s board of directors. A local businessman on the board had used the phrase while emphasizing the importance of providing the proper incentives for the doctors.

“It really took all of my self-control to not say, ‘What the hell do you mean skin in the game?’” he said. “We have our licenses, our livelihoods, our professions. Every single time we walk up to a patient, everything is on the line.”

He continued: “My thought was, I’ll put some of my skin in the game if you put your name on that chart. Just put your name on the chart. If there’s a lawsuit, you’re on there. You come down and make a decision about my patient, then we’ll talk about skin in the game.”

Amen.

As one of the Hospitalists involved in the organizing (and featured in the article) I would like to add that the reason for outsourcing was strictly financial. We were told by the VP of the medical group that “we want to get your cost down from 6 million to 3 million”. He stated that the numbers were not exact, but used as an example. When the Hospitalist program was reviewed by an outside company, their recommendation was outsourcing. There were no specific recommendations on how we could improve our program, and no opportunity to do so. Had they said “we will give you six months, three months, three days to fix your program”, etc, and we failed, then there would have been a justification for our outsourcing. The group was a phenomenal, hard-working, cutting edge Hospitalist program and it was destroyed by a CEO

who was hired to cut the budget. He also made it clear that we were the test group, and if this was successful, he was going to outsource first the Anesthesiologists and then the Emergency Physicians. Unionizing was the only way we had to protect our jobs and have a voice in the care of our patients. It was the only way we could protect ourselves and our practice from a corporate takeover. It has proven to be very effective, and we are hoping to be able to serve as an example that even small groups of physicians can successfully stand up to the corporations. I would encourage anyone who is in our situation to consider this as an option.

As one of the members who helped organize the union (and one of the Hospitalists featured in the article) I can say with clarity that the only reason for trying to out source our practice was financial. Our group was reviewed by an outside data company whose conclusion was that we needed to be managed by an outside management company. There were no recommendations about areas that needed improvement, no opportunity to correct any alleged shortcomings. Just a recommendation that we needed to be outsourced. (Whether or not the hiring of that specific company was due to the CEO being a member of the board of directors is unclear.) We were told by the VP of the medical group that “we are trying to get your cost from 6 million a year to 3 million”. (The numbers did not reflect actual budget, but were off the top of his head.) The CEO also stated that we were the test group. If this went well, he was then going to do the same to the Anesthesiologists and the Emergency Physicians. No metrics. No significant performance deficits. Just budget. We were never told what we needed to improve, and were never given an opportunity to improve our practice. It was a group of 38 extraordinary, motivated, progressive, cutting edge Hospitalists who were dedicated to the hospital and the community. None of us were ever interested or even very aware of unionizing prior to this, but felt that it was the only way we could protect our jobs and the patients we cared for. It was a very effective tool in being able to stand up to two very large corporations. It worked. We now have a very strong voice in our practice, and are getting close to having a decent contract that protects our individual judgement and provides safe staffing levels. While it was not a magic bullet to fix all of our ills, it gave us a voice and a leg to stand on. A place at the table, so to speak. I would encourage anyone who is in a similar situation to consider unionizing.

David M. Schwartz, MD

President

Pacific Northwest Hospital Medicine Association

AFT local 6552

Makes no sense. Hospitalists are in such high demand. If your reasonable requests are not met just walk away.

[…] hospital for outsourcing. Dr. John Nelson was quoted, and Dr. Brad Flansbaum followed up with a blog post reacting to the story on The Hospital Leader. The Wall Street Journal recently covered Journal of Hospital Medicine […]

Demand is huge. Just walk away. Administration feels they are better of with management company because of our are not seeing 16 patients per day.