After returning home from HM14, I reflected back on the talks delivered by Ian Morrison and (Sir) Bob Wachter. Without scratching below the surface, the takeaway message from both might accord with every industry prediction you read nowadays, mainly, tough times ahead, but “exciting” ones —because we need to transform how we deliver care. Moreover, the change agent will be you, Dr. Hospitalist. And we know you love change. Your DNA has change written all over it.

Both avoided fawning over accountable care and bundling as the saviors of our industry. Praise god. They had practical goals and dispensed a realistic prognosis for what might be in our future.

However, one thing did not hit home, and they both missed an opportunity to deliver an important point. While we are not frogs—and we will certainly do more than our share to improve hospital care—we are in hot water with the burners running.

We call the hospital home. Yet, every day the beast we slay—inpatient overutilization and excess—will ultimately lead to the deceleration and partial demise of our field.

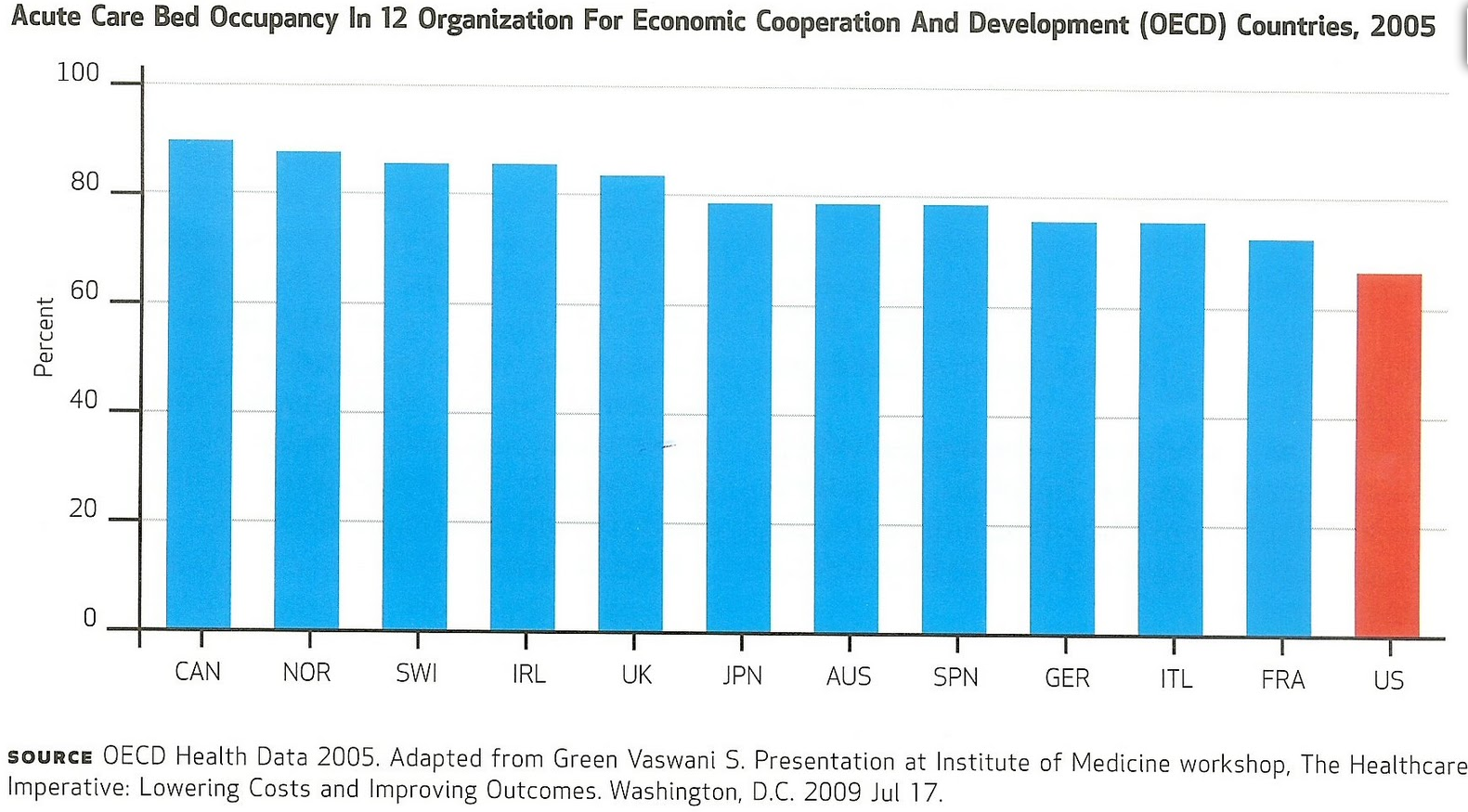

Do you know the hospital occupancy rate in the United States? We have trended down over the last decade as the guaranteed revenue streams from commercial and government payers have diminished. Our average hovers in the mid-60s, and as you can see relative to other OECD nations from nearly a decade ago, we lagged considerably. We have fallen further behind today. Excess beds do not bode well for hospital expansion and job offers (nor should they).

Need more?

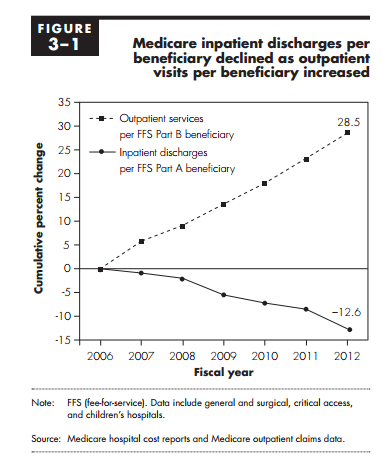

We all hear from the docs retiring, “we use to admit colonoscopies for 2-3 days.” Yes, that tired trope. However, what do you think you will be telling PGY1s when your social security check arrives in the mail? More than likely, nurses use to hang antibiotics in the hospital; the dialysis department had its own wing; and folks got admitted for poor glycemic control. While I am not a dyed in the wool believer of ACOs as beacons of population health, I do reckon the home will serve as a perfectly good vessel to deliver subacute and chronic care. You many not know it, but the trend has started post haste. Outpatient care has eclipsed inpatient growth for years:

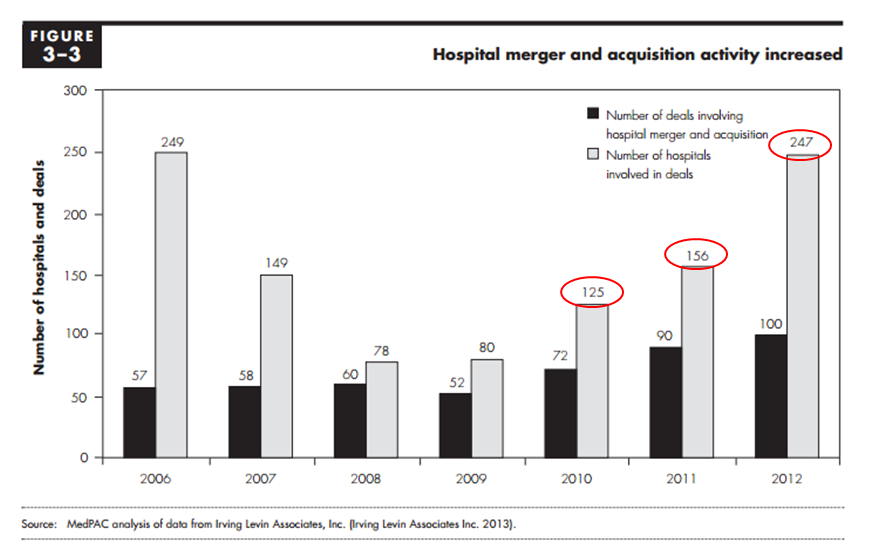

Perhaps you think the drift has not translated to hospital closures and consolidation. In fact, merged hospitals have become de rigueur. Currently, 60% of our nation’s facilities reside within a health system. The number of institutions involved in M&A activity has accelerated the last few years, and unless the FTC has something to say about it (they might), don’t expect a slowdown:

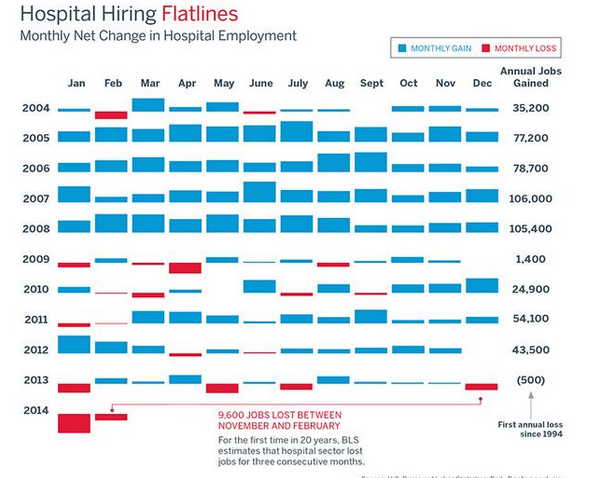

Finally, if you can sum up excess beds, decreases in inpatient admissions, and industry consolidation, the denouement unfolds without thought. What was a cash cow since the inception of Medicare fifty years ago, and what served as a job creating machine during frothy and rough economic times, has ceased to be. We can no longer feed the beast. You can see the long game below (h/t), and I don’t think you need translation: red equals more chuck, and a little less sirloin. I believe the trend will persist long-term:

Of course, you can interpret the above graphs in isolation or justify them away. You can attribute the findings to outdated information, overextrapolation, or statistical noise. Don’t! In aggregate, the trend will not be our friend.

Inpatient providers, good ones, will be change agents. However, when the change concludes, there will be less need for types like us—not because we don’t fulfil a greater good, alas we do, but because there will be fewer destinations for us to ply our craft.

While I do not personally know the two leaders you referenced, in general, leaders recognize the hot water we are in but do not dwell on it. There are many encouraging trends you have not mentioned like the increasing aged population who will likely convince politicians keen on re-election to not deny them care through ACA created panels. Our clinical and administrative roles in the hospital are constantly expanding while other physicians and administrators are leaving. At our same annual meeting I heard many leaders speak of new ways to “ply our craft” to hospitalized patient at their own home through interactive technologies. Leaders are optimistic about the future because we do not make linear assumptions from the past. Have faith we will continue to find solutions and provide innovative value as the future unfolds.

Eric

I am afraid your optimism will not overcome fiscal forces, even as technology improves (data sparse on “technology and innovation as big cost savers btw”) and limited administrative positions available to inpatient physicians open.

Hospitals do have bloat, and a lot of it. Care can be moved elsewhere with equally good results. Whether seniors will rebel, I cant say, but given their outsized say in DC, as they learn what the system can do outside of hospital walls, AND at lesser premiums (open wallet FFS wont continue indefinitely), the migration will occur.

Keeping hospitals alive should not be seen as a challenge, nor a reason to discover optimism or or faith. Like Microsoft inattentive to Google, we should not have blinders on. Its happening right now. Be prepared.

Brad

ps–the two guys you refer to: google. You might learn a thing or two re: above.

Wow!

I merely said I did not know Morrison and Wachter personally Dr. Flansbaum. I think most in SHM know of them and their contributions.

Eric

Not to distract from your point (which is both valid and immediate), but consider: when you draw the trend lines out even further, we will likely come to look back at our current hospitals with the same curiosity with which we regard the sanatoria and asylums of past eras.

“They put all of their sick patients, with whatever diseases they had, in the same building. Then they seemed surprised that patients left sicker, with illnesses they didn’t arrive with.”

Just food for thought for “futurists”.

Bob

I find Brad’s observations both timely and accurate. I was not able to attend this year’s SHM meeting in Las Vegas, but even last year Wachter was proposing that the strength and futurity of our profession rests in it’s malleability – the capacity to re-invent ourselves. Already some hospitalists are spending part of their time in outpatient extensivist clinics where they treat patients who could qualify for inpatient care but who may well avoid a hospital stay with a timely outpatient intervention. Why? Because a health system can save potentially several million dollars through such efforts. Some hospitalists are branching out as SNFist’s, spending time in a skilled care setting doing what? Managing patients several of whom might otherwise qualify for inpatient care but who can avoid a hospital stay from timely interventions pre-hospital.

What is our motive for these behaviors as hospitalists? Are we not actively assisting in the demise of our own profession? Only if we see ourselves narrowly as physicians who work solely within the walls of a hospital. The same skills we have developed to help our patients recover quickly from illnesses that require hospital care can (in the ACO world) be leveraged into a valuable commodity for those who would seek to keep patients out of hospital. And if we partner (or join) with an ACO, we stand to benefit perhaps even more that we could as minions of the local hospital. These are exciting times, filled with change and opportunity for those who are willing to grasp it.

Brad-

There is nothing to worry about. There are more jobs than hospitalists and way more jobs than highly skilled hospitalists. In my opinion, one of our biggest barriers as a “specialty” is that hospital medicine often serves as a refuge for poorly performing docs who cannot maintain an outpatient practice. Such docs can often move from desperate hospital to desperate hospital working in the inpatient realm. This is one of the dirty little secrets of hospital medicine and the most concerning in my observations over 16 years in the field.

I believe this time will be different because there is more emphasis on safety and quality but this reminds me of the 90’s. My first office as a hospitalist was in a patient room that had been closed since our hospital “needed to downsize due to the impact of managed care”. The room was spacious, had windows, and even oxygen for the really tough days. I got kicked out 2 years later when we needed to open up all our rooms due to overcrowding that began immediatelyafter the rooms were closed. Later a new bed tower was built. All the beds were full within months.

Another interpretation of some of the data you presented might be that countries with single payor systems have higher inpatient bed occupancy (and often longer LOS) and lower overall costs (and better outcomes). Why do we think that in the evolution of our healthcare system to look more like the rest of the developed world, we will see lower inpatient utilization with an aging population? Also, from an efficiency, quality, and safety perspective, optimal hospital occupancy is probably around 80%, not 100%. My hospital runs at 90+% almost all of the time. Any empty beds we have are not filled because we cannot staff them with nurses, not because we don’t have demand for them. I wonder how much that sort of thing impacts the occupancy rate numbers for the US as a whole.

@George Hoke

Thanks for the comment.

On intl comparisons, always fraught with peril–too many moving parts. Not a simple, “if x, then y” deduction.

I think with time, we’ll sort the HM wheat from chaff–certification and hospital consolidation will facilitate. The stronger will survive.

I dont know “ideal” occupancy rate balancing ROI and outcomes. Will vary with rural and critical access faciiities, along with other service lines for sure.

Brad

[…] Brad’s article – complete with lots of good graphs – comes from his perspective as a hospitalist, dissecting the trend towards an increase in outpatient care and a decrease in inpatient care. While outpatient care is probably more efficient, easier on the patient, and less costly (and certainly the way of the future given all of the medical technological improvements we’re seeing lately), it doesn’t bode well for hospital finances or hiring. We will always have a need for healthcare professionals, but as with any profession, those who can keep up with change will be the ones who continue to do well. […]