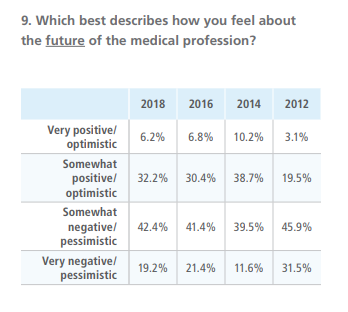

According to a new survey report released by The Physicians Foundation, 80% of physicians across all specialties report being at full capacity or overextended, and 78% reported sometimes, often, or always experiencing feelings of burnout. Sixty-two percent of U.S. doctors are pessimistic about the future of medicine, and 49% wouldn’t recommend medicine as a career to their children. This paints a pretty grim picture of medical practice in the U.S. in 2018.

The survey is conducted every other year by the Physicians Foundation with the assistance of Merritt Hawkins, and I wrote a blog post about the 2016 survey results, which showed alarming levels of disengagement and burnout. So I thought it would be worthwhile looking over the 2018 report to see if anything has improved.

The survey is conducted every other year by the Physicians Foundation with the assistance of Merritt Hawkins, and I wrote a blog post about the 2016 survey results, which showed alarming levels of disengagement and burnout. So I thought it would be worthwhile looking over the 2018 report to see if anything has improved.

It appears that things haven’t changed much for doctors since 2016 regarding their attitudes toward their work. The biggest take-away from this year’s survey is that doctors overall are working fewer hours and seeing fewer patients but still struggling with morale and burnout. One important trend that was highlighted is the move toward employment by hospitals or integrated delivery systems; only 31% of physicians are independent practice owners or partners, vs. 49% in the first such survey conducted in 2012. Interestingly, employed doctors tend to work longer hours but see fewer patients then their practice-owner colleagues.

The 39-question survey is sent out via e-mail to more than 700,000 physicians (everyone the AMA or Merritt Hawkins has in their database),  and this year 8,774 physicians responded; the statistics geniuses at the University of Tennessee say the survey results have a margin of error of +/- 1.057%. Interestingly, that’s less than half of the 17,236 physicians who responded to the survey in 2016, and I wonder if the reduction in response rate itself indicates an increased level of disengagement among doctors.

and this year 8,774 physicians responded; the statistics geniuses at the University of Tennessee say the survey results have a margin of error of +/- 1.057%. Interestingly, that’s less than half of the 17,236 physicians who responded to the survey in 2016, and I wonder if the reduction in response rate itself indicates an increased level of disengagement among doctors.

Doctors expressed similar frustrations with specific aspects of their work this year compared to 2016. The single biggest frustration cited by doctors was EHRs (39% this year vs. 27% in 2016), followed by regulatory/insurance requirements (down to 38% from 58% in 2016) and loss of clinical autonomy (37% vs. 32% in 2016). Survey respondents reported working an average of 51.4 hours per week, of which 11.4 hours (22%) are spent on non-clinical (paperwork) duties.

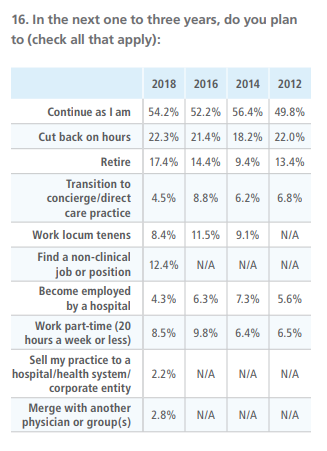

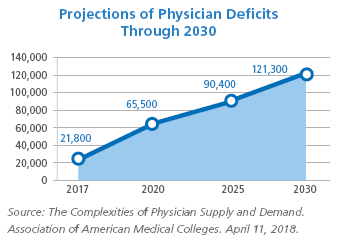

Alarmingly, about 46% of doctors reported making plans to change their career trajectory in some way, such as cutting back on hours or working part time (31%), retiring (17%), finding a non-clinical job or position (12%) or working locum tenens (8%). This has significant implications for physician manpower planning and healthcare access, and it’s interesting to note that the proportion of doctors reporting being at capacity or overworked has remained relatively stable since 2012 despite a significant increase in the deployment of nurse practitioners and physician assistants over that period. It’s not clear from these data whether the presence of NP/PAs doesn’t really help increase capacity much or whether their deployment just hasn’t been enough to offset the loss of physician FTEs to retirement, part time work, and movement into non-clinical jobs. The Association of American Medical Colleges has forecasted a shortage of up to 121,000 U.S. physicians by 2030, and physician shortages are already being felt in many or most non-metropolitan areas of the country – and even in some urban communities.

Alarmingly, about 46% of doctors reported making plans to change their career trajectory in some way, such as cutting back on hours or working part time (31%), retiring (17%), finding a non-clinical job or position (12%) or working locum tenens (8%). This has significant implications for physician manpower planning and healthcare access, and it’s interesting to note that the proportion of doctors reporting being at capacity or overworked has remained relatively stable since 2012 despite a significant increase in the deployment of nurse practitioners and physician assistants over that period. It’s not clear from these data whether the presence of NP/PAs doesn’t really help increase capacity much or whether their deployment just hasn’t been enough to offset the loss of physician FTEs to retirement, part time work, and movement into non-clinical jobs. The Association of American Medical Colleges has forecasted a shortage of up to 121,000 U.S. physicians by 2030, and physician shortages are already being felt in many or most non-metropolitan areas of the country – and even in some urban communities.

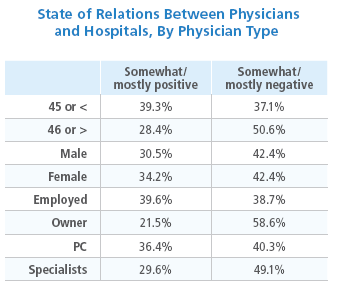

Among the most distressing findings for me, as a recovering hospital administrator, is that 46% of the respondents viewed the current state of relations between physicians and hospitals as  somewhat or mostly negative and adversarial. Owww! In addition, a majority of physicians (58%) are skeptical that the trend toward hospital employment of physicians is a positive one that is likely to enhance quality and decrease costs. And although 47% of doctors said at least some of their compensation is tied to “value-based metrics,” more than half (57%) don’t think value-based compensation is likely to improve quality of care or reduce costs. More broadly, 63% of doctors believe that physicians have little or very little ability to influence the healthcare system

somewhat or mostly negative and adversarial. Owww! In addition, a majority of physicians (58%) are skeptical that the trend toward hospital employment of physicians is a positive one that is likely to enhance quality and decrease costs. And although 47% of doctors said at least some of their compensation is tied to “value-based metrics,” more than half (57%) don’t think value-based compensation is likely to improve quality of care or reduce costs. More broadly, 63% of doctors believe that physicians have little or very little ability to influence the healthcare system

Unfortunately, the survey only categorizes physicians as either primary care (including family medicine and general internal medicine regardless of practice setting), or specialists. So there’s no way to know for sure how applicable these survey results are to the world of hospital medicine. But these results definitely resonated with me because I hear similar concerns expressed by hospitalists across the country. The good news, in a way, is that hospitalists are not alone. Your colleagues in other specialties are experiencing the same stresses you are. The bad news is, there aren’t any quick fixes to these issues, and it doesn’t appear that any of these trends will change soon.

So what can we do about all of this? There is no easy solution, but one important step is for each of us to work to ensure that our own practice environment (our hospitalist group, our hospital or health system, our personal and family life) is taking the issue of physician wellbeing seriously. Is your hospital or medical group taking proactive steps to address very real and pressing issues of workload and work redesign across specialties and care settings? Does your hospital have an active physician wellbeing committee, and is the committee taking concrete action to promote recognition and appreciation, workplace social cohesion and occupational solidarity, improved conflict management skills, peer support, work-life balance and other important aspects of physician wellbeing – rather than just being a body that deals with the fallout of all of this: individual physicians who have behavioral or substance abuse issues? Is your HMG constantly working on ways to better support efficient, rewarding hospitalist practice? Is it developing creative strategies to enable part-time work and/or job enrichment? And are you personally pursuing self-care strategies that can increase your resilience, and including your family and friends in your self-support efforts?

For those of you who have success stories in how your organization or group (or you personally) have successfully addressed some aspect of overwork or burnout, we’d all love to hear about them. Please join the conversation and share your experiences by commenting below.

I worked for an organization with an EMR with such inadequate servers that, when I bailed, I was spending 2 hours a day staring at a frozen screen. They had no intention of fixing things. They lost half their docs in 6 months and still didn’t move to change. Community Health Centers maintain an avowed strategy to prevent seniority raises: alienate docs by keeping them out of the decision making process, fill vacancies with J1 visas and new grads. I locumed at very different organization which profited from maintaining physician satisfaction (they made sure we were done at 5) .

Another locum brought me into contact with a caring, effective administrator brought in by the umbrella organization, to replace the administrator who drove off 6 of 7 docs. My tenure ended with successful recruitment.

The bottom line: some organizations learn from experience, some don’t. On a personal basis, I will try to reason with management exactly once before I bail.

Exactly as I had felt when I was in solo practice and retired 15 years ago. Sad to see the disengagement is worse now. I was fortunate to have been in solo internal medicine where no one told me what to do and I did not do EHR.

I retired early.

I started as a Family Physician in 1987. I was a full partner in a small single specialty group. We were the largest group in a small town and we very

much were a power in the local 47 bed hospital. Very little computer control of medicine yet and I practiced full spectrum Family Medicine. I always sat

on the Executive Committee of the local hospital and did my turns as Chief of Staff. In the mid-90s,, a local hospital chain allied with our hospital and

not much changed. Then a much more aggressive hospital chain took over, fired a large part of the hospital employees, built a new hospital on the edge

town,and built a Medical Office Building next to the hospital, and my practice was offered the whole ground floor in 2000. My partners were overjoyed

and I,the eternal skeptical one, perceived we had moved into a “gilded cage”. I was right, the Lease destroyed us financially as planned.

In 2004, I left my partners behind to struggle on until they sold themselves to the hospital chain and I reinvented myself as a Hospitalist. My first Hospitalist

job lasted 10 years, until a new, young administrator decided we were not making the hospital enough money and ended the program. EHRs were now fully entrenched

and in my last year of employment at the hospital, I survived the agony of a cheap, buggy, forever failing EHR system covered up with lies. It was am older, no longer

supported, cheaper version of the chain’s EHR.

I was tossed out like dirty laundry water at age 59. I decided I still wanted to retire early, so I went on to the local VA Hospital as a Hospitalist and I hoped to put 5

years in so I could retire with VA insurance benefits. It was not to be. The VA system grinds people up with tremendous layers of bureaucracy, and physicians are

not very valuable employees. I was treated like any other employee and was bullied by my supervisor as all the other women on the service were. Pharmacists, RTs,

and nurses argued orders and too many were incompetent. Most nurses has gone through online training with virtually no real clinical experience. The doctors were being replaced by NPs and the NPs were covering the ICU without backup most nights. In early 2018, I fired the VA 20 months short of 5 years so I had to take Obamacare. I had to take care of my mother in the late stages of her dementia and I wanted to enjoy my farm while still young. I left while I was still at the top of my game with no history of malpractice suits or any disciplinary actions.

I loved medicine. It was good for my soul, but medicine left me. Doctors gave up most of their power and large corporations without an ethical foundation and no god but money took over. NPs are cheap and doctors harder to control.

Now I try not to let people I meet know I am a physician.

situation is dire but they are waiting so all the senior physician will retire. Nurses will become leaders who will follow administrations lead and control physicians. Money and cost cutting is the major driver. Physicians are not valuable anymore because they have different opinions which cost a lot. There is a lot of window dressing but they actually don’t care. They just want to run a business