There are a limited number of things in hospital medicine that we do that decrease the risk of all-cause mortality by up to half. Usually these are the type of things that we don’t even think about possibly missing. Does your hospital give people with STEMIs an aspirin? Even that has a number needed to treat of 42. Do you treat pneumonia with antibiotics? Good.

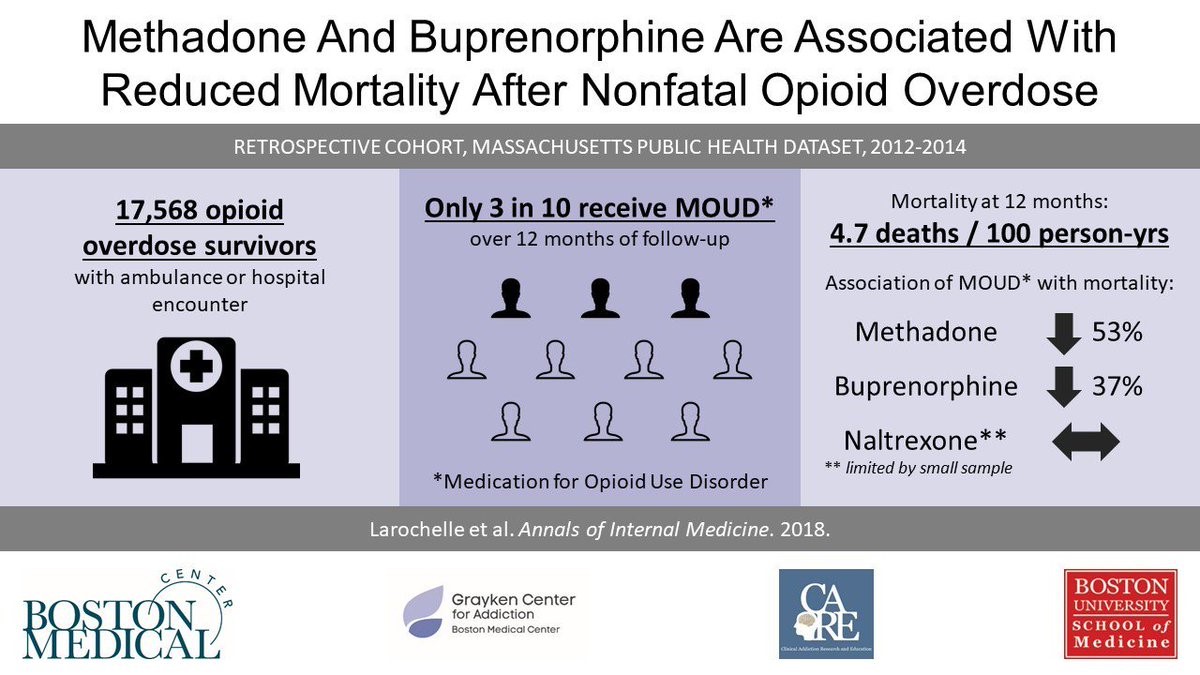

A study published earlier this year in Annals of Internal Medicine found that treatment with buprenorphine or methadone after a nonfatal overdose was associated with a 40-60% reduction in all-cause and opioid-related mortality. Yet only 3 in 10 of these patients received medications for opioid use disorder over 12 months of follow-up. We – our medical system – had a whole year after these patients OVERDOSED to treat their problem, and for more than half of them, we didn’t even try.

It is increasingly clear that this is the epidemic of our time, with new numbers released last Thursday from the CDC that show drug overdoses set another troubling record, with more than 70,000 Americans died in 2017. As the New York Times put it, “overdose deaths are higher than deaths from HIV, car crashes or gun violence at their peaks.”

Visual abstract from @AnnalsofIM

Alright, let’s put aside the patients admitted with overdose for a minute, because sometimes that is hard to pin on the hospitalist who may have only seen them briefly. How about all of those patients we treat on hospital medicine with complications of opioid use disorder – the patient with active IV drug use admitted with infective endocarditis or vertebral osteomyelitis, who you have on your service for 6 weeks while they receive IV antibiotics through a PICC line because you can’t send them out with a line and they won’t get accepted to any post-acute facility. Surely during those 6 weeks you address the real reason they are there, right?

In a great article from JAMA Internal Medicine (“Treating the Symptom but Not the Underlying Disease in Infective Endocarditis: A Teachable Moment”), the authors point out:

“Just as a patient with heart failure is admitted with acute decompensated heart failure, infective endocarditis from IV drug use secondary to OUD [opioid use disorder] represents acute decompensated substance use disorder. When a patient with heart failure is admitted with an exacerbation, the medical team identifies causes of the exacerbation, titrates evidence-based medications, and proactively works to prevent future hospitalizations in the transition to outpatient care. Meanwhile, when someone with OUD is admitted with endocarditis, too often the cause of the exacerbation is deemed to be a moral failing, antibiotics are administered, and abstinence is recommended.”

A retrospective study at a large academic hospital in Boston looked at the care and outcomes of 102 patients admitted with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Addiction was mentioned in 56% of discharge summary plans, yet only 8% of patients had a plan for medication-assisted treatment. About a quarter of patients died over the 10-year study period, with a median age of 40-years-old. Theoretically, that hospital alone could have saved about 10 young lives if they had treated patients with buprenorphine or methadone.

In another study hot off the presses from JAMA Network Open, referral to addiction treatment in patients who use injection drugs and had infective endocarditis was associated with a significant mortality benefit (HR, 0.29; 95%CI, 0.12-0.73; P = .008).

In addition to apparently saving lives, medication-assisted therapy leads to increased completion of inpatient medical therapies (patients are less likely to leave AMA). After discharge, they are more likely to transition to outpatient substance abuse treatment, and less likely to engage in criminal activity related to illicit opiate use.

Which makes me think, if we are not treating opioid use disorder during hospitalization at this point, is it malpractice?

Well, not yet, particularly considering the barriers to medication-assisted therapy induction in the hospital remain substantial. Most hospitalists and other clinicians are often not comfortable dealing with opioid dependency beyond acute withdrawal symptoms. A stigma exists both around patients with opioid dependency, as well as with its primary treatments such as buprenorphine. Nonsensically, I could prescribe a ludicrous amount of opioids if I wanted with very little oversight, but I need a special X-waiver to prescribe Buprenorphine. (X-waivers can be obtained with eight-hours of training and the options for attending a convenient training session are increasingly available).

An even bigger issue is this sort of work cannot be tackled by individual hospitalists. It requires systems-level interventions to ensure community transitions, as well as available MAT and professional counseling. Linkage to outpatient providers and services is particularly critical and can be challenging to establish. This is why at other hospitals this has not been taken on by hospital medicine groups, but rather as hospital-level projects. And generally the services have been provided by addiction medicine specialists. However, considering the scope of the opioid epidemic this is a non-scalable solution. This would be as if during the 1980s and 1990s we relied ONLY on board-certified HIV specialists to treat HIV.

Up until now, I have not actively treated opioid-use disorder in the hospital. However, thanks to efforts from my colleagues, such as Rich Bottner PA, now I will. Rich and Dr. Nick Christian (one of our “Distinction Track in Care Transformation” resident physicians) worked, along with others, to start “The B-Team” (Buprenorphine) at Dell Seton Medical Center – a multidisciplinary team that accepts consults for inpatients with opioid use disorder and can meet with patients, discuss therapy with them, initiate buprenorphine when appropriate, and make a warm hand-off to a partner outpatient clinic for ongoing care. Unlike other efforts we know of, this team is hospital medicine-led and integrated into our work.

The B-Team is new, but as we gather more experience, I look forward to sharing what we learn. One of the biggest areas of early work for this group that has arisen is a focus on reducing stigma and communicating and spreading an approach to opioid use disorder as often a chronic and potentially relapsing disease that warrants long-term treatment, rather than something that should simply be dealt with through a short-term intervention such as withdrawal and encouraging abstinence.

You don’t have a B-team yet? I believe soon enough, this will sound like saying you just don’t have a cath team for patients with STEMI. You and your hospital should get started. Ensuring timely and capable transitions to outpatient care will not be easy. Starting an uninsured patient on Coumadin for pulmonary embolism and ensuring timely follow-up is also not easy, but we regularly take on that problem. Convincing your hospital to invest in this care will not be easy, but it is critical. If doing the right thing is not motivation enough for them, perhaps the promise of reducing readmissions will help. Especially for those of us who work at safety net hospitals, I believe this is shaping up to be a key challenge of our time.

Great perspective contrasting our resistance to considering buprenorphine/naloxone for inpatients with our willingness to prescribe other completely unaffordable life-saving drugs with no guarantee of continued therapy or outpatient follow up. Creating a B-Team is a brilliant idea. While any prescriber can initiate or continue buprenorphine/naloxone for hospitalized patients at risk for withdrawal, regardless of waiver status (see https://www.samhsa.gov/programs-campaigns/medication-assisted-treatment/legislation-regulations-guidelines/special), that freedom ends when the time for discharge prescriptions arrives. A multi-disciplinary focused approach will serve patients well.

As someone who has taught the waiver certification course, I can assure it’s an easy first step to being able to provide patient-centered care for those with opioid use disorders. I would encourage any hospitalist to take advantage of the opportunity to bring this expertise and skill to working with their systems to create their own standardized process for providing continuous high-quality care – and literally saving lives.