This past year, I reviewed a lot of journal articles to prepare for the Updates in Hospital Medicine talk with Dr. Carrie Herzke at Hospital Medicine 2019. But for the last six weeks or so, I simply monitored the headlines to ensure there wasn’t a blockbuster finding that we would have to integrate last minute into our talk.

Now, like a marathoner who took a break after the big race, I am slowly lacing back up my sneakers and hitting the road. So tonight, I opened up that overflowing folder of journals and got to reading… and reading… and reading. I immersed myself in the characteristically masterful Lisa Rosenbaum three-part NEJM series on teamwork. I tried to parse the results of the JAMA catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation studies. I read about low-value care, and also about how using an online platform to pool diagnoses of multiple physicians into a ranked list could improve diagnostic accuracy.

All of this was rather fascinating, but after the electronic dust settled, I found the most relevant clinical take-aways were all related to confronting one of our most rivaled and common clinical foes: sepsis.

To save you time and PDF downloads, let me share with you, Updates-style, the three things I just learned about sepsis that suggest ways we may approach this disease in the future.

1. Monitoring capillary refill might be a better strategy than using lactate for resuscitation

Over the past 5+ years, we have adopted using serum lactate as the principal marker for adequate resuscitation. This was codified in the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Guidelines, which recommended measuring serum lactate every 2 to 4 hours until normalization. There are many problems with this, including that lactate can be elevated for other reasons besides hypoperfusion, it can be relatively slow to clear, it requires a lot of lab draws, and could possibly be leading to too much fluid resuscitation.

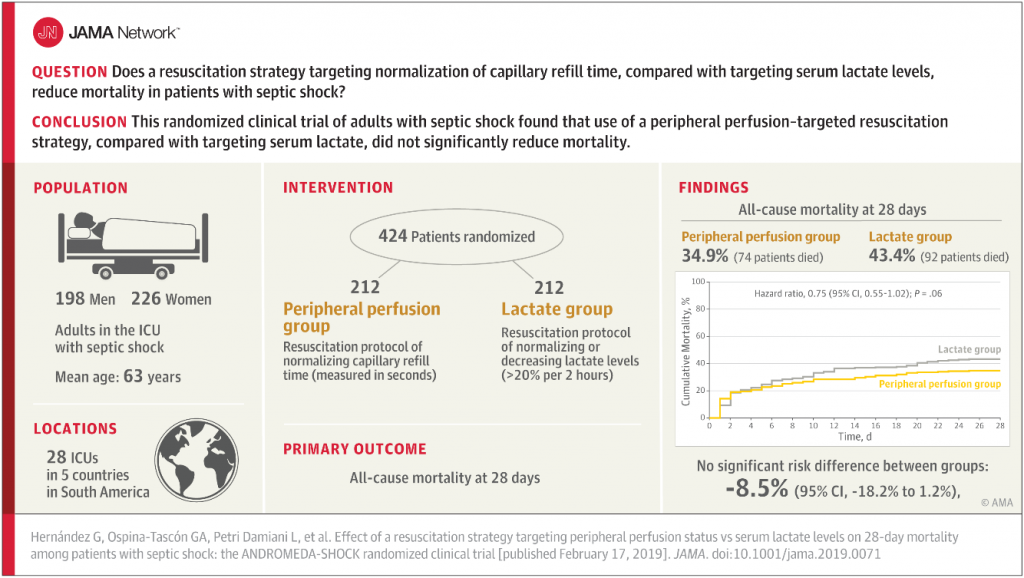

Could simply targeting capillary refill time work as well – or maybe even better – than serial serum lactate measurements? I had never considered it before, but the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK trial published in JAMA asked that question and the results are intriguing.

This was a multicenter randomized-controlled trial in 28 ICUs across 5 countries, in which 212 patients were assigned to serial lactate measurement protocol (as per current standard of care), and 212 patients were assigned to a peripheral perfusion protocol with the goal of monitoring capillary refill every 30 minutes and targeting a capillary refill time of less than 3 seconds as the marker for resuscitation adequacy. All of the patients were adults in the ICU with early septic shock.

There was no significant difference in all-cause mortality at 28 days. In fact, the capillary refill time group had a LOWER mortality rate that nearly reached statistical significance (p=0.06), suggesting it is possible (though unproven at this point) that this strategy could actually be superior to lactate measurement.

Also the capillary refill time group had less organ dysfunction at 72 hours, and for patients who had a baseline SOFA score under 10, the capillary refill group had a significantly lower 28-day mortality.

It makes sense because capillary refill time is going to respond to resuscitation more quickly and can be measured more frequently (without invasive intervention) than serum lactate measurements.

One other important note: of course, they did not measure capillary refill time like I do – I push on the fingertip until it blanches and then eyeball the response time. That’s what you do too, right? They applied a microscope slide to the finger pulp for 10 seconds and then counted the time to reperfusion with “a chronometer,” which I have to admit I thought must be a fancy instrument but according to Google this basically just means an accurate watch.

It is too early to call this practice changing, but it certainly is exciting and I suspect we will start to see a lot more studies of this strategy. I, for one, will likely begin checking cap refill in my septic shock patients, along with lactates for now. I may even begin carrying around a microscope slide in my pocket to make it look like I am doing something a bit more sophisticated than pinching their finger and then staring at it.

The study: Hernández G, Ospina-Tascón GA, Petri Damiani L, et al; ANDROMEDA-SHOCK Investigators and the Latin America Intensive Care Network (LIVEN). Effect of a resuscitation strategy targeting peripheral perfusion status vs serum lactate levels on 28-day mortality among patients with septic shock: the ANDROMEDA-SHOCK randomized clinical trial. JAMA. [published online February 17, 2019]

2. We should probably start norepinephrine earlier in septic shock

In septic shock, it is rarely clear when exactly we should change tactics from giving more IV fluids to starting a pressor.

In this single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in a hospital in Thailand, adult patients with sepsis and hypotension were randomized to either receive norepinephrine (norepi) or placebo early along with fluid resuscitation. If they remained hypotensive after receiving at least 30ml/kg of fluid, then open-label vasopressors were permitted regardless of which arm they were assigned.

Those assigned to the early norepi group received the drug a median of 93 minutes after arrival at the emergency department, whereas the other patients did not start pressor therapy until a median of 192 minutes.

The early norepi group patients seemed to do better, with 76% achieving shock control by six hours compared to 48% in the standard therapy group. They also had lower incidence of pulmonary edema (14% versus 28%; p=0.004) and new-onset arrhythmia (11% versus 20%; p=0.03). There was a non-significant difference in 28-day mortality, 15.5% in the early norepi group and 22% in the standard treatment group (p=0.15).

Once again, we will need more evidence beyond a single-center study, but as we increasingly recognize all of the deleterious downstream effects of fluid over-resuscitation, this does seem to make sense.

It seems like these studies may be a glimpse into how we will approach sepsis in the future. Future-me may be targeting early norepi and capillary refill times, instead of bags and bags of IV fluids and serum lactates. My remaining question – does early norepi administration effect capillary refill time? What will my future-self do then?

The study: Permpikul C, Tongyoo S, Viarasilpa T, et al. Early Use of Norepinephrine in Septic Shock Resuscitation (CENSER) : A Randomized Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Feb 1. [Epub ahead of print]

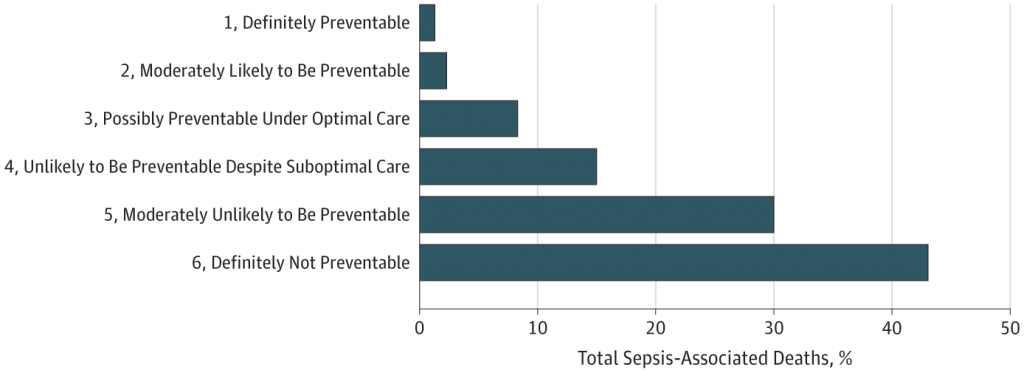

3. Up to 88% of sepsis-related deaths are not preventable, even though there are often potential areas for care improvement

Ok, so now we have been looking at potential new ways to optimally treat sepsis in the future. How many more lives will be able to save? A rather sobering article from JAMA Open suggests that it might not be as many as we would hope. They found that nearly a quarter of patients in this study received suboptimal sepsis care (e.g. delayed antibiotics, source control, or inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy), yet 88% of sepsis-associated deaths were still deemed unpreventable when reviewed by study investigators.

This is likely because patients with sepsis often have other serious underlying life-limiting conditions, such as metastatic cancer.

So no matter what new strategies we adopt in the not-so-distant future, it seems like sepsis will probably remain one of our most feared and humbling adversaries.

The study: Rhee C, Jones TM, Hamad Y, et al. Prevalence, underlying causes, and preventability of sepsis-associated mortality in US acute care hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187571.

Leave A Comment